Site Links

The Great Journey

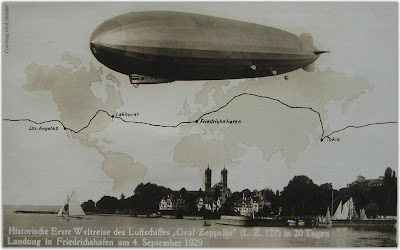

In world gripped by economic unease and international strife, the Graf Zeppelin’s epic expedition transfixed the planet. Engineered largely by the media empire of Randolph Hearst through the intrepid reporter Karl von Weigand, the Graf set out on an unprecedented journey by air around the Earth.

Hearst, who had secured exclusive media rights, insisted the voyage begin and culminate in the USA, so the established base at Lakehurst, New Jersey was used. This meant the Graf must fly from its home base of Friedrichshafen in Southern Germany to the USA and back, so in effect there were two round-the-world-journeys in one.

The celebrity entourage included Dr Hugo Eckener as commander, Lady Grace Marguerite Hay Drummond-Hay (the only woman) and Karl von Weigand reporting for the Hearst network along with recently knighted Australian explorer, Sir George Hubert Wilkins. In all, ten nations were represented including Spain, Japan, Russia and France, comprising sixty-one passengers and crew.

Great hopes were placed on the voyage. Not purely from a technical point of view, but from a political one as well. The world was still smarting from the destruction and upheaval of the Great War and would shortly endure enormous hardship in the Great Depression. Even so, thousands of well-wishers and media turned out to farewell the mighty dirigible on the evening of August 7 as it set out on its history-making odyssey. As the ship sailed smoothly off to the east, it seemed to many as if it was carrying the hopes of the world with her. “… a flight into uncertainty …” said the normally precise Dr Eckener.

Three days later it was back in Friedrichshafen refuelling and resupplying before setting off toward Russia, across the foreboding Siberian plains toward Tokyo. For many hours the passengers would look down upon endless miles of remote forest knowing that if a forced landing were necessary, hope of rescue would be nil.

Lady Hay sat at her typewriter, staring out across the empty landscape, quite likely amongst the first human eyes to ever see much of it. “It seems like a dream,” she wrote in her report to Hearst, “indeed it is a dream – a dream of man’s ambition to conquer the elements, to conquer space, to conquer nature’s barriers, which since the world began have effectively segregated the races and the peoples of the nations.”

During the day peasants ran in terror and animals fled in panic as the monstrous vision appeared overhead; a great silver fish swimming almost silently through an endless ocean of air with just the faint whirr of propellers to break the silence.

After a leg of 7000 miles and 102 hours, the Graf Zeppelin arrived to a tumultuous welcome in Tokyo. An equivalent journey by sea would take a month while the trans-Siberian Express over a fortnight. Commercial transcontinental air travel had arrived, effectively shrinking the size of the world.

In Tokyo a quarter of a million frenzied Japanese turned out to greet the ‘zepp’. Eckener knew what was coming and the entire complement of passengers and crew were thrown into a maelstrom of civic receptions, banquets and media events. This part of duty he referred begrudgingly as, “the difficult social and political obligations.” So many gifts and souvenirs were received, they had to be crated and sent ahead by steamer.

As the Graf set off to the USA, the end was coming into view. Yet even as the mooring lines were being stowed, fixed wing aviation was moving ahead in leaps and bounds. Heavier-than-air contraptions were now crossing the Atlantic and flying non-stop across America. An RAF fighter reached 350mph. Despite the undeniable grace and majesty of the airships, conventional aircraft were catching up.

As the verdant panorama of an adoring Japan faded from view, Lady Hay offered this farewell;

“We have just come out of a beautiful dream, a flowery Utopia, where everyone is kind, smiling, kind, helpful and courteous … it is a happy world – this world of the Zeppelin.”

In a cruel irony, Lady Hay and Karl von Weigand became prisoners of the Japanese after being captured in the Philippines in 1942 while filing for Hearst. Although released at the end of the war, she died very soon after from exhaustion and fatigue.

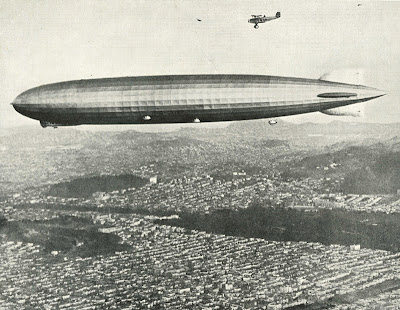

On the 25th of August, the first crossing of the Pacific by air was completed and San Francisco rose to a man to welcome the world’s greatest air adventurers. Eckener risked his world record time by diverting to Los Angeles to salute his patron before landing – or trying to land. The unusual air phenomenon in Los Angeles had created an inversion that cooled the ship’s gas and forced it up again. Vast quantities of valuable hydrogen had to be released to force it down. Eckener knew this would create a reverse problem on take-off and he was right.

Aircraft escort the Graf Zeppelin as it approaches Los Angeles after crossong the Pacific Ocean

“We sail tonight,” announced Eckener, with the record in sight, cutting the stay to just one day.

With the usual barrage of press and newsreels in attendance, Eckener persuaded the Graf to lift off, but he could see trouble ahead. He gained speed to try and get aerodynamic lift, but the beast would not rise, instead bouncing along the field as excess provisions were hurled unceremoniously out the galley door by the cook to lighten the load.

Ahead loomed menacing high tension wires that must be cleared and Eckener pulled back on the controls, forcing the tail into the earth and leaving a deep trench. The tail still would not rise and the wires loomed closer. Eckener made a spilt-second decision to “jump” the wires like a hurdler and as the nose cleared the wires he thrust the craft down to raise the tail. “Clear behind” came the call from the crew in the stern and he pulled the controls up again to level off. They cleared the wires by a bare metre, and continued on to New York, leaving passengers gasping for breath and counting their lucky stars.

Fortunately the damage was relatively slight and the ship continued on its way, via Detroit and Akron to New York and at just after 8 am on August 29, the Graf Zeppelin landed in world record time. Flying time: 12 days and 11 minutes. Total elapsed time: 21 days 5 hours and 35 minutes. Both world records.

The excitement in New York continued for days and the crew and reporters, particularly Lady Hay, were mobbed wherever they went. With this single endeavour, Eckener had reasserted Germany’s national pride, not as a war-monger but as a unifying force for peace and goodwill. Even one passenger, Lt. Commander Kusaka of the Japanese Navy remarked with palpable irony; “If nations could get on like that, there would be real hope for permanent peace.”

More >> The Fall from Grace

|

All

material, unless otherwise noted, is copyright to the author and

may not be used, reproduced or mirrored without express consent

in writing. Permission is not specifically sought for linking, although

the author does appreciate notification.

|