Escape from PNG: The Bulldog Track

Longer, higher, steeper, wetter, colder and rougher than Kokoda

How a bunch of fugitive old miners and tradesmen discovered a vital supply route and survived one of WWII great escapes.

Roderick Eime learns about The Bulldog Track from the book by actor, Peter Phelps.

The legend of the Kokoda Track has long since entered the annals of Australian folklore. The decisive and protracted battle marked a turning point in the war against the invading Japanese but, despite its unarguable importance, the Kokoda Campaign runs the danger of overshadowing many other significant battles and exploits.

The Battle of Milne Bay, the Battle of the Coral Sea, the bombing of Darwin and the Australian triumphs in Borneo and Bougainville are just a few instances where our confrontations with the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and navy (IJN) had important influences on the final outcome of World War II in the Pacific.

So too, the many exploits of regular civilians and minor players in this massive conflict went overlooked, such as our earlier feature on the small ships, drawn from pleasure craft and fishing boats, that brought crucial supplies to our forces in the earlier stages of the war and the toll on the old men and boys who served on these tiny vessels.

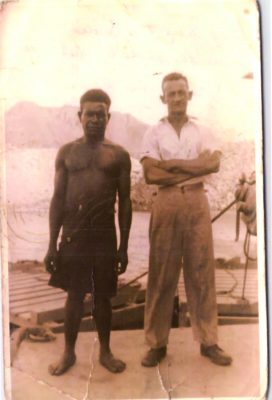

Australian film and television actor, Peter Phelps, has authored one such book that tells the tale of his grandfather, Tom, who was too old to enlist but was still caught up in the cut-and-thrust of the New Guinea battles when he and 200 fellow civilian employees of the Bulolo Gold Dredging Company, with their escape routes blocked and their aircraft destroyed, had to flee from the brutal onslaught of the Japanese invaders as best they could.

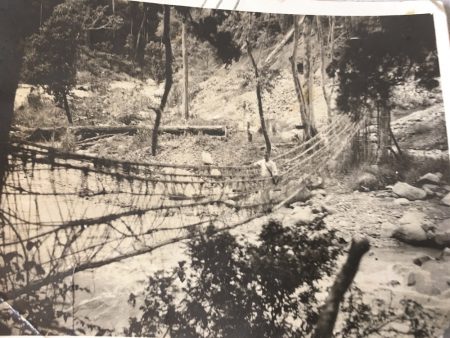

The men hurriedly abandoned their mining site at Edie Creek (about 50kms SW of Lae) at 11 p.m. on the 4th of March 1942, destroyed everything they could and made their way south, over the treacherous Owen Stanley Ranges on a rough path that became known as The Bulldog Track, later described by the author, spy and newspaper journalist, Peter Ryan, as “longer, higher, steeper, wetter, colder and rougher than Kokoda.”

"They were civilians; gold miners, carpenters and all sorts of trades. So there was nothing documented about these guys," Peter Phelps explains. "It was such a time of war that a couple of hundred miners' story would just not be considered because it wasn't part of the war effort. But they were as brave as any soldier."

Phelps delves into his family history and recalls the tales of his father and grandfather and the effect their experiences had on forming the strong fibre of the Phelps family who hailed from the Sydney suburb of Punchbowl. Researching the book was not easy either as very few records of their escape existed. One unlikely source came in the form of his grandfather's hat which Tom had kept with him throughout the ordeal.

Most of what information that was recorded was contained on his grandfather's battered pith helmet, along with a rudimentary map he'd scrawled on baking paper, recording dates and locations including where his dead companions were buried. That and a letter he wrote to the editor of The Sydney Morning Herald in 1944, comprise the entire firsthand history of the Bulldog Track.

Tom Phelps passed this information on to the authorities when he finally reached Port Moresby and a vital supply road was built along the path he had surveyed. The road took eight months to complete and was hailed, at the time as one of the greatest feats of military engineering.

The Chief Engineer, W. J. Reinhold, later wrote "Every foot of progress made on this road exacted the ultimate in courage, endurance, skill and toil. Its construction took a toll from surveyor, engineer, labourer and native carrier alike."

During one five-month period of construction, more than two-thirds of the crew contracted malaria and it wasn’t until September 1943 that the first vehicles were able to make a clumsy passage along this perilous route.

Phelps Snr was also lavish in his praise for the native ‘bois’ who had guided them along the way, doubtlessly a vital part of their success and survival.

“This book is not a work of fiction,” writes Peter Phelps, “it is a tribute to the resilience and strength that saw my grandfather survive, and his family hold together while he was gone. It is a tribute to all those who survived the Bulldog Track.”

Doing the Bulldog Track

If you thought Kokoda was a pushover, then you could raise the bar with a trek along the Bulldog. While no commercial operator currently offers guided tours along the track, there is numerous notes and guides available to anyone who wanted to mount their own, self-guided expedition.

Situated some 200 km west of Port Moresby, the track crosses the Owen Stanley Range peaking at about 2600m altitude. It connects Wau in the Bulolo Valley with the Lakekamu River on the south side and can be done in either direction. The track will take you about a week to walk, depending on your level of fitness, plus about two days for the transport from Port Moresby to Lakekamu River.

You can find more detailed trekking notes at: www.real-adventure.info

Tom's letter

Tom's letter to the editor, published in the Sydney Morning Herald on May 29, 1944:

Sir—

The article by Edward Axford (SMH, 20/5/’44), on the building of the Bulldog Road, made known the part played by the men who blazed the trail from Wau and Edie Creek to the Papuan coast by way of Bulldog and the Lakekamu River. Being one of the original party who left Edie Creek at 11 p.m. on March 4, 1942, I can fully substantiate all he says in regard to the hardships endured. I was working on the Bulolo goldfields when the Japanese attacked New Guinea by air on January 21. They destroyed our company’s three planes on the ground at Bulolo, making our evacuation by air impossible. Two days later we proceeded by road to Wau in the hope of being evacuated by air. Again our hopes were dashed by being bombed twice in a week. Now hopelessly cut off from Port Moresby and our own people, we moved up the mountain to Edie Creek. It was from this place that we hatched our plans to go overland by this unknown trail in the hope of reaching the coast of Papua. So we set out a few nights later with very little food and a few of the natives, to whom most of us owe our lives. I should also like to express my gratitude to Dr Giblin, an elderly man, who did everything possible, under terrible conditions, for the sick and injured. We eventually reached the coast very much the worse for wear, I having lost 4st on the journey. We then walked 60 miles down the beach to Yule Island, and later by schooner to Port Moresby, where we gave all the necessary information to the authorities which probably prompted them to build the road. The task they performed can only be appreciated by those who travelled the trail through this country.

THOMAS PHELPS

Punchbowl