Wrangling Wrangel - Words and pics by Roderick Eime

As published in Vacations & Travel [PDF] 600kb

Wrangel Island is an enigmatic landmass trapped in the fringes of the permanent Arctic ice pack. Born out of legend and maintained by tales of hardship, endurance and tragedy its apparently austere appearance hides a UNESCO World Heritage-listed, self-contained island ecosystem.

Giant snow-capped mountains rose magnificently into the crisp polar air, perhaps thousands of feet high, while shimmering lakes bordered by lush forests carpeted the land. Despite this idyllic vista, all before him was frozen solid, an impenetrable carpet of sea ice.

The

year was 1821 and Baron Ferdinand Petrovich von Wrangel (right) had been

with his dogs on the ice for many months in search of the fabled lands

hundreds of miles north of Siberia. Thwarted from setting foot on this

mysterious nirvana by the permanent ice that so effectively isolates the

Arctic island, the Baron was, in fact witnessing a fata morgana: a complex

mirage created by light passing through the cold arctic air.

The

year was 1821 and Baron Ferdinand Petrovich von Wrangel (right) had been

with his dogs on the ice for many months in search of the fabled lands

hundreds of miles north of Siberia. Thwarted from setting foot on this

mysterious nirvana by the permanent ice that so effectively isolates the

Arctic island, the Baron was, in fact witnessing a fata morgana: a complex

mirage created by light passing through the cold arctic air.

It wasn’t until 1849 that British Naval Captain, Henry Kellett named it for himself and the Crown, only to have it renamed by American whaler Thomas Long in 1867 who thought the Russian was more deserving. From that moment on, Wrangel Island has been a point of contention between Russia, Britain, Canada and the United States. Despite a series of multi-national flag-raisings over a period of fifty years, it is only now that the international community seems to have acquiesced to Russian sovereignty.

Perhaps Wrangel Island’s ridiculously remote location in the perpetually ice choked Chukchi Sea north of Siberia makes it something of an unattractive proposition. So, in July 2005, I set out aboard the giant Russian icebreaker, Kapitan Khlebnikov, to see what all the fuss was about.

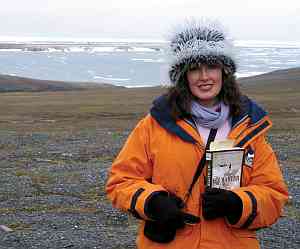

Along

for the ride as a guest lecturer was author Jennifer

Niven (left) whose two critically-acclaimed books, Ice Master

and Ada Blackjack zero in on Wrangel Island as an epicentre of

hopelessly misplaced optimism and tragedy. Her laboriously researched

and superbly written books trace in detail the vain efforts of Canadian,

British and American explorers and “scientific colonists”

to extract some profit from the land – monetary, political or intellectual.

Along

for the ride as a guest lecturer was author Jennifer

Niven (left) whose two critically-acclaimed books, Ice Master

and Ada Blackjack zero in on Wrangel Island as an epicentre of

hopelessly misplaced optimism and tragedy. Her laboriously researched

and superbly written books trace in detail the vain efforts of Canadian,

British and American explorers and “scientific colonists”

to extract some profit from the land – monetary, political or intellectual.

Standing on the deck, I watch the mighty Kapitan slice through irregular slabs of sea ice with relative ease. Even with a fearsome “ice knife” in the bow and 25,000bhp available to drive it home, we are occasionally forestalled by a particularly stubborn sheet. One, perhaps a metre thick and about the size of a city block, brings us to a noisy, shuddering halt. The Kapitan, unfazed, backs up and body-slams the floating mass, opening a fissure that gradually opens to admit our 15,000 tons of diesel-electric anger.

The waters through the notorious Bering Strait had been relatively ice free for most of the voyage, but then dense ice, interspersed with leads kilometres wide, shields Wrangel Island from the mainland – and from lesser equipped vessels trying to make landfall there. It was precisely this phenomenon that thwarted seafarers for well over a century and prevented the rescue and resupply of the hapless souls marooned there nearly a century ago.

These

ice floes are also the domain of the many mother polar bears occasionally

seen leading their first season offspring across the pack in search of

seals. The denser the ice, the more the bears like it. Bears can’t

catch seals in the thinning floes because the seals can easily escape

into the water. I take my turn on bear watch, camera primed for the elusive

shot.

These

ice floes are also the domain of the many mother polar bears occasionally

seen leading their first season offspring across the pack in search of

seals. The denser the ice, the more the bears like it. Bears can’t

catch seals in the thinning floes because the seals can easily escape

into the water. I take my turn on bear watch, camera primed for the elusive

shot.

During our lectures, Jennifer had passionately recounted the tale of Ada Blackjack, the sole survivor of Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s crazy attempt at colonising the island in 1921. After the failure of the resupply ship, she watched the three fit men set off to Siberia for help while she nursed the other suffering from scurvy. The trio disappeared into a snow storm and were never seen again. Her patient, quickly failing, died some weeks later.

It was five days from the port of Anadyr in Chukotka Province before we had our first glimpse of Wrangel Island, dull and foreboding through thick, wet arctic mist. Far from welcoming, this island was one of the ‘jewels’ described by the imaginative Stefansson as a paradise teaming with game and resources. Sure, Wrangel Island can boast the largest population of denning polar bears, a few reintroduced reindeer and Musk Oxen, arctic fox, walrus and seals. Birds are abundant too, especially the over-protected Lesser Snow Geese (Anser caerulescens), which, our Russian hosts assure us, flock in large numbers in the west of the island. Regrettably, we are not permitted to visit them.

I’m beginning to think the Baron would have been a bit disappointed with his discovery had he actually made it thorough the tortuous miles of pack ice. Stefansson too may have privately moderated his enthusiasm if he had actually seen the land for himself. But there’s no mistaking the journey, one of the most difficult and unpredictable of the era, there’s a palpable sense of satisfaction amongst the passengers and crew, especially Jennifer, who appears to be almost channelling Ada at some points.

We explored what appeared to be a featureless landscape by both motorised zodiac and the Kapitan’s mighty MI-2 jet helicopters. Our first landing was to see a herd of Musk Ox, gathered on the windy tundra and enjoying a family picnic amongst the bright pastel sprays of arctic wildflowers. Wrangel Island actually has more vascular plants than any arctic island, over 400, with 23 endemic species. This display had the plant people quite excited, and it was common to see well-insulated posteriors pointing skyward as they arranged their cameras for precision macro photos.

Instead,

my mind imagined the forlorn souls trapped here and forced to eke out

a living by hunting anything and everything. They ate polar bear, foxes

and even grass to survive. Jennifer too, normally ebullient and vivacious,

was strangely silent as she pensively kicked pebbles on the beach in her

trademark leopardskin gumboots.

Instead,

my mind imagined the forlorn souls trapped here and forced to eke out

a living by hunting anything and everything. They ate polar bear, foxes

and even grass to survive. Jennifer too, normally ebullient and vivacious,

was strangely silent as she pensively kicked pebbles on the beach in her

trademark leopardskin gumboots.

In 1923, her heroine, alone and scared after the death of her only, sickly, companion, had to learn to hunt ducks with an unfamiliar rifle, trap foxes and overcome her debilitating phobia of polar bears. We all tried to imagine being alone on this treeless land for months on end, foraging, hunting and just surviving. Two days were all we had to synthesise this isolation, and by the time we set a course south again, our attention was diverted to the parties of men who made the crossing of Long Strait (to Siberia) on foot.

Apart from our intrepid Baron, who made three trips out onto the ice, each involving many hundreds of miles, three other journeys deserve recounting.

On a beautiful clear January day in 1923, three brave young men set out for Nome, via Siberia, from Wrangel Island to get rescue. Ada Blackjack bade them farewell and wished them, silently, good luck. Allan Crawford, Milton Galle and Fred Maurer were never seen again. In a strange irony, Fred Maurer had been one of Bartlett’s men rescued in 1914. Such is the lure of the arctic! In

1881, the thirty-three shipwrecked survivors of the USS Jeanette

dragged seven tonnes of stores and three heavy boats across the ice until

they could finally launch them in an attempt to reach the mainland. A

storm separated them, one boat was lost and the other two struggled ashore

in the Lena River delta on the Siberian mainland. In the inhospitable

cold, only thirteen men were eventually rescued.

In

1881, the thirty-three shipwrecked survivors of the USS Jeanette

dragged seven tonnes of stores and three heavy boats across the ice until

they could finally launch them in an attempt to reach the mainland. A

storm separated them, one boat was lost and the other two struggled ashore

in the Lena River delta on the Siberian mainland. In the inhospitable

cold, only thirteen men were eventually rescued.

In

1914, in one of the arctic’s most enduring tales of survival, Captain

Bob Bartlett (right) and an Inuit hunter made for Siberia from Wrangel

Island on foot to get rescue for the fifteen men left on the island. Nine

months later, a schooner he sent from Alaska picked up twelve survivors

and for a few fleeting days, the heart-warming tale displaced the horrors

of the First World War from the front pages of the nations’ newspapers.

In

1914, in one of the arctic’s most enduring tales of survival, Captain

Bob Bartlett (right) and an Inuit hunter made for Siberia from Wrangel

Island on foot to get rescue for the fifteen men left on the island. Nine

months later, a schooner he sent from Alaska picked up twelve survivors

and for a few fleeting days, the heart-warming tale displaced the horrors

of the First World War from the front pages of the nations’ newspapers.

With the smooth, flat landscape of Wrangel Island slowly disappearing amid a lingering polar sunset, we leave behind this renowned nature reserve, repository of legend and lore, natural wonderland and kingdom of sadness and despair. Clearly, despite earlier valiant efforts, Wrangel Island will never be inhabited, left instead to the occasional scientific observer and the capricious devices of nature. A good thing too.

|

Background Image by Runic.com

Fact

File:

Fact

File: