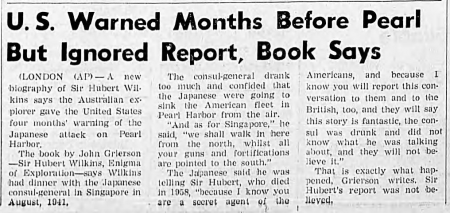

Did an Australian adventurer and spy forewarn of the attack on Pearl Harbor?

Battleship USS West Virginia sunk and burning at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. In background is the battleship USS Tennessee.

by Roderick Eime

The story begins aboard the 1929 round-the-world flight of the German airship, LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin.

A truly international contingent of media and privileged guests are enjoying the lavish facilities of Germany’s luxury airship as they complete their ground-breaking three week journey around the planet.

Among the media contingent is the recently knighted Australian celebrity explorer and cinematographer, Sir George Hubert Wilkins, who is reporting for the vast Hearst newspaper network.

Round-the-world voyage of the Graf Zeppelin (LZ-127): Japanese passengers of the Zeppelin in a Tokyo teahouse - 1929. Wilkins is in the rear, while Lt. Cdr. Ryunosuke Kusaka kneels in front. (ullstein bild)

In the spirit of international co-operation, the guests enjoy polite conversation and genuine camaraderie. German, Soviet, Japanese, American, British, Spanish, Swiss and French guests all gather politely for dinner and relaxation in the lounge during the long voyage.

The two Japanese military observers, Lt. Cdr. Ryunosuke Kusaka and Lt. Cdr. Fujiyoshi warm to the amicable Australian and all become good friends. The group are feted like royalty when the airship arrives in Tokyo.

Fast forward ten years and Wilkins is on a thinly disguised espionage mission and meeting with senior Japanese diplomats in the Raffles Hotel, Singapore. Wilkins had already been in China, Japan and Asia gathering information and it was clear to him that war in the Pacific was inevitable. His Japanese contacts had been very forthcoming with aircraft production data and information in 1929, but now in 1940, they were convivial, but tight-lipped on such matters.

Between times, Wilkins had attempted to take a modified WWI submarine beneath the polar ice cap. The 1931 so-called ‘Nautilus’ mission ended in failure and embarrassment for Wilkins.

In the famous bar in the Raffles Hotel Singapore, Wilkins is enjoying drinks with the Japanese Consul General, who he had met ten years prior in Tokyo, when the conversation becomes ‘fluid’. His drinking pal suddenly drops a most intriguing piece of information.

Famous Long Bar at Raffles where Wilkins heard the astonishing news of the impending attack on Pearl Harbor

“I know what you’re doing here. You’re not on any economic survey, you’re working for the US Government,” said the inebriated diplomat, “Now I’ll tell you something you don’t know. Eighteen months from now we will attack the American fleet in Pearl Harbor.”

Wilkins reeled at the disclosure. “Where did you get such an idea and why are you telling me this?”

The well-lubricated consul burst out laughing and challenged Wilkins to go ahead and make his report, winding up the explorer by saying “they’ll never believe a man who was crazy enough to try to take a submarine to the North Pole!”

Given Wilkins’ excellent personal connections, the idea was not as preposterous as it sounded, and he did go ahead and make his report. Sure enough, his warning was ignored or discounted as implausible. Either way, Wilkins warned the US of an impending attack on Pearl Harbor at least 12 months in advance.

Ironically, his Japanese friends would go on to play important parts in the attack. Ryunosuke Kusaka was named the chief of staff of the Japanese Navy Combined Fleet and was critical in the planning of both the Pearl Harbor and Midway attacks, while Vice-Admiral Akira Fujiyoshi rose to Head of Aviation for the Japanese Imperial Navy. Both survived the war.

Numerous theories exist about ignored intelligence and advance warnings that were discounted by the White House for any number of reasons, with most pointing to the US secretly wanting a reason to enter into full-scale war with Japan as was being urged by Churchill. The fact that the all-important US aircraft carriers were absent on the morning of December 7 is most noteworthy. Yet few of these apparently ignored warnings were delivered as early as mid-1940, when Wilkins delivered his. *

* Some sources say Wilkins was in Singapore in 1941